French

Villages Salute Their Liberators

by

Ted Heck

We waved back as President Chirac of

France led the parade from the Arc de Triomphe down the Champs Elysees

to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Victory in Europe.

Thousands of French men and women jockeyed for position along the

temporary fences that lined both sides of the wide boulevard. Waiting

imperiously at the bottom was the statue of General de Gaulle.

Connie and I stood with other spectators

for three hours to see horse cavalry, military bands, and delegations

from other countries pay tribute to the end of World War II and to the

men and women who made victory possible.

I was in France on the first VE Day in

May, 1945, and had looked forward to being here for number 60. The

French celebrate the day every year, but this one was special. A CNN

reporter later that night said it was doubtful that many veterans of

that war would be around for the 70th anniversary. At age

83 I wince every time someone points out that we’re dying at the rate

of 1,100 a day.

The Paris commemoration was repeated

throughout the day across France. In Reims, site of Germany’s

unconditional surrender, dignitaries had spent three days in

celebration. VE Day was the raison d’etre for the start of our

two-week journey into the past that got more personal in

Alsace-Lorraine on the German border. We connected with my “band of

brothers,” who saw combat there.

The Paris commemoration was repeated

throughout the day across France. In Reims, site of Germany’s

unconditional surrender, dignitaries had spent three days in

celebration. VE Day was the raison d’etre for the start of our

two-week journey into the past that got more personal in

Alsace-Lorraine on the German border. We connected with my “band of

brothers,” who saw combat there.

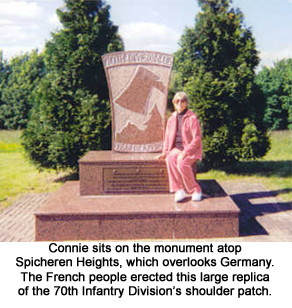

A tour group of 63 visited a half dozen

villages that were liberated in January through March, 1945, by

members of the 70th Infantry Division. Twenty-one of them

were fellow veterans; the others were their children and grandchildren

who had come to see where their elders’ defining moments had occurred.

The trip, part war recollections, part sightseeing, had been arranged

by California tour operator Floyd Freeman, himself a member of the 70th

Division.

(“Band of brothers” is a motto of our

Trailblazer division. We borrowed it from Shakespeare long before

historian Stephen Ambrose did. Henry V motivated his troops at

Agincourt: “ We few, we happy few, we band of brothers, for he that

sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother.”)

Before we caught up with the group, my

fiancée Connie and I spent several days recapturing the magic of

Paris. We sauntered along the Seine, gaped at masterpieces in the

Louvre and D’Orsay museums, read the International Herald Tribune on a

bench in Tuileries garden, dined in charming restaurants with an old

friend of Connie’s, who lives in Paris.

We rented a car from Avis, paying for

additional insurance not covered by credit card. I had had sad

experiences before with tailgating French drivers. It was a 300-mile

trip to Alsace-Lorraine on the high-speed, toll-heavy autoroute. We

went by Reims and famed battlefields of World War One---Chateau

Thierry, Verdun and Metz. The country side was lovely, with its

rolling hills, dense forests, and high meadows that were often patched

with fields of yellow rape flowers.

The battle sites we headed for had names

anonymous to most Americans; names such as Forbach, Behren,

Grossbliederstroff, and Spicheren. They‘re in the northeast corner of

Lorraine, near the German industrial city of Saarbrücken, which the

division captured in late March. We also visited Wingen sur Moder and

Philippsbourg, in the mountains some 30 or 40 miles south. If the

villages sound Germanic, it must be remembered that Alsace-Lorraine

bounced back and forth between France and Germany over the years. Most

of the older population speaks two languages.

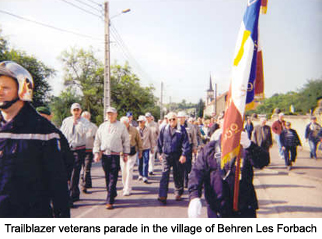

Michael Obiegala, mayor of Behren Les

Forbach, set the theme and tone of the days that followed. After a

parade to a monument to our division---each village has a stone or

tablet that honors us---he read in French, followed by an English

translation. He stressed the debt his village owed us.

“It was simply the biggest humanitarian

operation of all times…it will remain forever, a large feeling of

gratitude.”

After the ceremony we reminisced over

lunch with a large crowd of locals, some old enough to remember the

frightful time. Others had heard of us from their parents.

Schoolchildren participated in the salutes, more aware of history than

American teenagers who are more likely to relate to "Star Wars."

In every village the busload of veterans

and families was followed by vintage jeeps and trucks and soldiers in

uniform. But these were Alsatians and Lothringers wearing army

uniforms with our Trailblazer insignia. They are the Amis, a group of

men and women who keep memories of us alive---and reenact war games on

old battlefields.

Connie got caught up in the festivities

and was overwhelmed to hear various versions of our combat

experiences. She wept in the U.S. military cemetery in St. Avold,

largest in Europe with more than 10,000 graves. According to American

director Marcel Millet, there had originally been 90,000 buried

abroad, but most had been repatriated at the request of their

families. Connie took a photo of me beside the grave of fellow

lieutenant Bernie Brons, killed on a patrol that

could have been assigned to me. It was a moment to reflect on what

Bernie had missed in six decades--and to feel a twinge of guilt about

being a survivor.

versions of our combat

experiences. She wept in the U.S. military cemetery in St. Avold,

largest in Europe with more than 10,000 graves. According to American

director Marcel Millet, there had originally been 90,000 buried

abroad, but most had been repatriated at the request of their

families. Connie took a photo of me beside the grave of fellow

lieutenant Bernie Brons, killed on a patrol that

could have been assigned to me. It was a moment to reflect on what

Bernie had missed in six decades--and to feel a twinge of guilt about

being a survivor.

Later in the small public cemetery in

Philippsbourg Connie clicked other photos, while I talked with a man

roughly my age. He was replanting flowers on a family grave of his

wife and her parents. I told him that I had slept there, too, when my

mortar section fired projectiles from the cemetery---hidden from

retaliation by a steep mountain. Our foxholes were dug between graves.

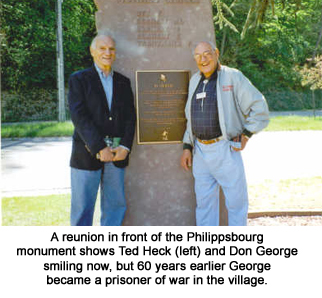

Philippsbourg was the most vivid visit for

me. It was where my regiment first met the German army. We were

ambushed on New Year’s Day, a greeting from elements of the 6th SS

Mountain Division. The village didn’t have a hundred homes, but it was

an important road junction for the Germans. They had failed in the

Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes to the north, but they had one

last gasp, Operation Northwind, designed to go through the

snow-covered Vosges Mountains toward Strasbourg. We were in their way.

We gave the village back and forth in 10

days of fierce fighting, in bitter cold conditions with daily

temperatures in single digits. We held them off at great cost in

killed, wounded, or evacuated with trench foot.

…………

…………

There was a sad moment later when two

women on the trip asked me to pinpoint where their father/grandfather

had been killed.

In the village of Grossbliederstroff,

following a salute to us in the main square, we visited a small museum

residents had created. It contains uniformed manikins, equipment,

weapons and ammunition.

We

adjourned to the village of Lixing for still another salute and a

joyous dinner. Yes, joyous. There were many solemn moments, but

tributes were often complemented by merriment. None of us will forget

a youth choir’s asking us to join them in singing “My Bonnie lies over

the ocean.”

Food is always a dominant part of a

journey in France and an inducement to turn conversations to happier

times. In Alsace we drew smiles when we ordered jellied pork and the

natives’ favorite sauerkraut dish. When Connie and I were on our own

and not being entertained by the villagers, we ate simply, sometimes

even sandwiches in a McDonalds.

But

we also dined well; the chef owner and his charming wife in the Hotel

de la Marne in the spa town of Morsbronn les Bains served us an exotic

dinner by candlelight. They were so proud of their kitchen that a

monitor in the main dining room allowed guests to kibitz the food

preparation.

At a subsequent meal in a delightful

restaurant in Strasbourg, Connie just had to have foie gras,

assuming perhaps that she would get a dollop of it on a wafer. She

gasped at the slab put before her---the size of a thick slice of

Wonder Bread. She barely touched her second course.

Food costs in France are high. Even in

rural taverns l’addition commands a second look. Service is

included, but the French tax on food of 19.6 percent negates any

desire to tip. The foie gras lunch, with dessert, had a tab of

$95.

Lodging in neat, comfortable, three-star

hotels was generally under $100 a day. For the room--but breakfast was

often outrageous. Our Paris hotel room cost $75. Petit dejeneur

was $42 extra. We ate several breakfasts in our room with items

purchased in a local supermarket.

However, we could not save on gasoline. We

paid more than five dollars a gallon in traveling 1,000 kilometers

(620 miles). The only solace was learning that, if we were smokers,

that’s what we would cough up for a pack of cigarettes.

Connie was enthralled by the delayed

replay of the war, but also enchanted by the countryside, particularly

small villages with colorful, half-timbered houses. I had to remind

her that much of what she saw was robed in white during the 1944-45

winter---and looked far less inviting.

We picked Strasbourg, capital of Alsace

and headquarters of the European Union, as an ideal place to wind

down. The cosmopolitan city near the Rhine River blends the Middle

Ages with modern commerce and geopolitics. We visited the magnificent

cathedral that dates back to the 12th century and spent an

afternoon in the three museums of the adjoining Palais Rohan---beaux

arts, decorative arts and archeology. But mostly we wandered, even in

the rain, among gingerbread houses in the oldest part of the city. We

saw them again as we circled the city on a sightseeing boat on the Ill

River.

“Aren’t you glad we came?” Connie asked.

“It’s too bad your family wasn’t here, too, to share these moments

with you.”

“Aren’t you glad we came?” Connie asked.

“It’s too bad your family wasn’t here, too, to share these moments

with you.”

Strasbourg was a fitting place for me to

end the memory junket. Sixty years earlier Generals de Gaulle and

Eisenhower were at odds on whether to defend the city, if the Germans

tried to reoccupy it. De Gaulle prevailed and Ike agreed to hold back

the enemy by beefing up forces in the region.

That was big picture stuff. The 70th

Infantry Division played a small but important part in it.

Ted Heck enlisted in the army as a

private, returned to college as a captain. He values most his combat

infantryman badge, but he also won a Silver Star in Philippsbourg and

two Bronze Stars and an Air Medal in later action.