Fighting World War II with Family

By Ted Heck

|

Southern California 25, Tennessee 0. This summer I finally learned the score

of the 1945 Rose Bowl.

My nephew Doug plugged in his laptop and Googled the result as we sat in a

restaurant recently in the village of Philippsbourg in Alsace Lorraine. We

were in France during a family visit to my old battlegrounds.

It had been 64 years since I sat under a huge rock on New Year’s Day and

wondered about the game, to take my mind off the predicament I was in. Our

rifle company had just been ambushed by German infantrymen as we marched

along a road in the dark. We had sought refuge on a promontory in the woods.

Doug knew more than that score. He had brought with him large contour maps

that he pulled from the Internet. He and his teenage son Adam and brother

Jim were able to find my long-ago rocky haven and even spot some leaf-filled

depressions that might have been our foxholes. Doug was able to identify the

area where one of our squads had been captured during the night and also the

route we took as we fought our way back to the village in the morning.

|

|

I have returned to Philippsbourg several times over six decades, mostly in

reunions with comrades. Once to a dedication of a monument to the 70th

Infantry Division (Trailblazers). The stele is one of many tributes to us in

villages we liberated in the first three months of 1945.

This visit, however, was prompted by my younger brother Bill’s desire to see

for himself the sites I often talked about. He had seen a video interview I

did for the American Institute for History Education, an organization that

feels today’s teachers know little of what I call the “last of the

respectable wars.”

Bill, his sons and grandson flew to Germany from Texas, I from Philadelphia.

We picked up a van in Frankfurt and spent a day in Heidelberg, much of it

among the ruins of the castle that looms over the historic university city.

It was the right antidote for jet lag and a sleepless night on the long

flights.

We did not need Doug’s map to get across the Rhine River into France. The

van’s GPS system guided us to Hagenau, the spa town of Niederbronn,

Philippsbourg and the nearby hamlet of Baerenthal. Although one battalion of

our 275th Regiment had fought fiercely in Baerentahl, our focus on this trip

was on Philippsbourg. Our 3d Battalion and specifically my Company K spent

two weeks there fighting house-to-house and repelling tank attacks.

In one incident artilleryman Pfc George Turner, 45-years old and a veteran

of the first World War, stood in the middle of the street with a bazooka and

knocked out two German tanks. He won the Congressional Medal of Honor for

his bravery.

The fighting was fierce here because Philippsbourg was a main intersection

between two peaks in the heavily wooded Vosges Mountains and important to

the Germans in their drive southward toward Strasbourg.. They had just lost

the Battle of the Bulge, but had one last gasp: Operation Northwind, led by

Volksgrenadiers and elements of an SS mountain division, who were accustomed

to fighting in the snow.

Doug, a student of various American wars, used one of his maps to pinpoint

the cemetery where some of my men had dug their foxholes among the graves. I

had spent a night or two with them, shivering in the snow. (Daytime

temperatures rarely got into double digits.)

My family laughed when I recalled dining in the cemetery on steak and French

fries which the platoon cooked up, after they dispatched a wounded cow. A

sergeant butchered the animal, his men scrounged potatoes from a deserted

cellar and they used their helmets as pots. Soldiers took turns coming from

their frontline posts for a meal that did not come from a can or box.

The village’s main attraction for my family was the monument to our division

that stands tall in front of the town hall. But they were also interested in

the church that served as a first aid station. They explored pillbox ruins

from the Maginot Line, the ill-fated defensive line that could not hold the

Germans back when they invaded France in 1940.

We had lunch at Café Falkenstein, situated at the main intersection and were

delighted when its owner Patrick brought out his scrapbook.

A former mayor of the village, he has memorabilia about our 70th Infantry

Division Association, including items from the days of combat and photos of

numerous veterans who, like us, have come back to relive the time. (Our host

at the Hotel Kirchberg in Baerenthal, Veronique Loeb, is the daughter of that

village’s former mayor. He, too, has a scrapbook, a chronicle of the action

there, which he witnessed first hand.)

We moved on to many other villages that are forever grateful to our

division. Lixing and Grosbliederstroff were scenes of costly attacks. In the

latter Christophe Ultsch, Frenchman but an associate member of our division,

is custodian of a museum dedicated to us. We spent an afternoon examining

his exhibits, particularly photographs of some of my friends. His impressive

arsenal of pistols, grenades, rifles, and machine guns were handled by all

of us. Unlike most museums, this was a “Please Touch” one.

|

|

|

|

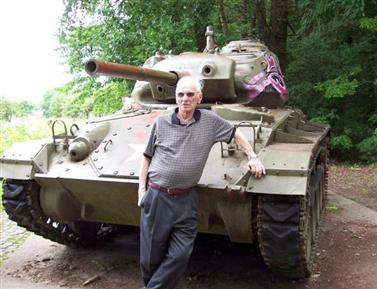

Ted in the museum

|

A Heck of a gang. Front: Adam and Doug

Rear: Jim, Bill, Ted and Todd on Spicheren Heights

|

The most dramatic tribute to our division is atop Spicheren Heights. It is a

huge marble replica of our shoulder patch: red, white and green colors in

the shape of an axe, with a pine tree and snow-covered mountain. It

symbolizes our Trailblazer nickname. Nearby is a tank that the U.S. Army

donated to the community.

Bill on Spicheren Heights |

I described to the family how we had stormed through smoke to reach this

area, which had fortifications of the Siegfried Line, protecting the

city of Saarbrücken. Jim, Doug and Adam went down into bunkers we had

assaulted. War historian Doug took time to study other monuments in the

forest: many are dedicated to soldiers who fought in the Franco-Prussian

conflict in 1870. It reminded us that this region of France had changed

hands and was sometimes part of Germany.

Our family group grew when my son Todd and his wife Maureen joined us

for two days. They had been on holiday, bicycling along the picturesque

Moselle River before catching up with us.

During our combat-oriented itinerary we had many humorous moments:

family memories, anecdotes about friends and relatives. But nobody

laughed in the military cemetery in St. Avold. The largest U.S. military

cemetery in Europe has 10,489 graves. It once held more than twice as

many, but those casualties of war were repatriated to America at the

request of their families. There are 150 unknown soldiers buried here

and four Medal of Honor winners. The Walls of the Missing has 444 names

of men whose bodies were never recovered. |

Valerie Mueller, administrative assistant, led us among the rows to find

several graves I wanted to see again. She carried with her a bucket of wet

sand from Omaha Beach, which she rubbed on the tombstones’ indented names to

make them stand out in photographs. We stopped at the grave of Bernard Brons,

a fellow lieutenant who was killed leading a patrol that could have been

assigned to me. We also visited the grave of Bill Beck, with whom I went to

college, and John Lally, a high school classmate.

The fierce fighting of Philippsbourg and Baerenthal was attested to here by

a printout Valerie gave us. There are 39 members of the 275th Regiment

buried in St. Avold. Twenty-seven of them died in the first 10 days of

January, 1945.

Historians Donald Pence and Eugene Peterson wrote of this period in their

“Ordeal in the Vosges” book. Their numbers for the regiment: a third of our

3,000 men were killed, wounded or missing in action, or evacuated with

trenchfoot and frozen extremities.

I came close to being under one of the crosses. In March when we walked into

the city of Saarbrücken with no opposition, I volunteered to scramble over

the rubble of a bombed bridge in the Saar River to question several

civilians visible on the other side. They told me, and I yelled back to the

commanding officer, that the German soldiers had pulled out the day before.

When I crossed back over the river, I asked a sergeant to give me a hand

getting up the bank. I grabbed his carbine by the barrel and he was pulling

me up when the gun went off. The bullet skipped through my belly and into my

leg like a flat stone thrown on the water. I was the only casualty and my

war was over.

I spent six weeks in the hospital before returning to duty. During my stay

the hospital’s head doctor came to the ward to present me with a Silver Star

I had won for leading an attack in Philippsbourg in January and a Bronze

Star for capturing nine Germans hiding in a cellar in Etzling in late

February.

He also handed me a Purple Heart, which I refused. I was embarrassed enough

by such a weird version of friendly fire.

My family wanted to see exactly where this had happened. We drove up and

down along the river, but Doug’s maps couldn’t help. A superhighway now

dominates the riverfront, so the group had to believe my memory and my

scars.

After Saarbrücken we drove through the rolling hills of western Germany to

the spa town of Bad Kreuznach and on to Bingen on the Rhine River. We spent

the final day of our action-packed itinerary on a river cruise up to the

town of St. Goar, past steep terraced vineyards, the rocks of the Lorelei

legend and castles that seemed to float by every 10 minutes.

A relaxing day, yet one in which the family still asked questions about the

war. Brother Bill had come up with the idea of this remembrance of war and

insisted that we were all his guests. He had been in the Army, too, and

wanted to be an infantryman. He was in Officer Candidates School at Fort

Benning, Georgia, when the war ended.

The family grasped both the big and the little picture of World War II. The

big picture of generals who dealt with campaigns, strategies and logistics.

And the little picture of simple soldiers whose concerns were scarier and

had shorter timetables.

I was moved by the family’s interest in this dramatic period of my life.

They plan to share it with others in videos that Jim and Doug recorded as we

covered the ground.